From Oaxaca to California

By Paul Amico

When Gabriel and Esperanza Flores left their home in Santiago Juxtlahuaca, Oaxaca, Mexico, to come to sunny Southern California in June of 1985, they had many goals and aspirations in mind.

The decision to leave, while difficult, was made in order to give their future family more opportunities. During this time, Mexico was in the midst of an economic crisis, resulting in the family making the decision to leave behind friends and family. The family settled in Riverside, California before eventually moving to Nuevo, a small town in Riverside County.

“To us, there was no other option but to coming to the United States,” Gabriel Flores said. “We knew we were going to have a family, so we wanted the best for our future children, and we felt like that was in California.”

The pair were two of approximately 1.1 million who naturalized in the United States from Mexico between 1980-1989, according to migrationpolicy.org.

According to California State University, Northridge Chicano/a Studies Professor Xóchitl Flores-Marcial (no relation to the family), who was born in Tlacolula de Matamoros, Oaxaca, the fall of the Mexican peso in the 1980s resulted in a huge economic crisis that led to a flood of people coming across the border.

A second reason for the large migration, according to professor Flores-Marcial, was the civil wars that erupted in Central America in the 1980s.

“Many people came [to the U.S.] during that time of the crisis, partially because of the civil war happening in Central America, which had an influence on the Mexican economy, politics, and people’s migration,” professor Flores-Marcial said.

Three decades later, Gabriel and Esperanza Flores’s sacrifice to come to California paid off. The family has raised five children in Riverside County, all of whom have grown up to become successful adults.

The oldest, Freddy (29), was the first in the family to graduate from college, earning his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from California State University, San Bernardino. Eduardo (26, bachelor’s in business) and Berenice (24, bachelor’s and master’s in Business and Human Resources) soon followed, while Jennifer (21, Health Administration) currently attends Cal State Northridge and Gabriel Jr. (19) attends Riverside Community College.

The ability to attend college and earn a degree has allowed the siblings to achieve success in the workplace. For Jennifer, the only one of her siblings to move away from home to attend college, her education has opened up a wealth of jobs, internships,

and mentors.

“My family’s culture is something I hold very close to my heart.”

-Berenice

“The amount of opportunities I’ve been given since I came to college have been endless,” Jennifer said. “I have an internship at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center and at the Simi Valley hospital. I also conduct research at my university on hospice care in the Latino/a community. It makes me appreciate even more the sacrifice my parents made to give my siblings and I

this life.”

As far as her other siblings, Freddy works for the state of California as a State Parks and Recreation Ranger. Eduardo is the Human Resource director of a local dairy farm in Riverside county and is in the process of joining the United States Marines. Berenice works at the San Bernardino Police department as a Personnel & Training Technician and Gabriel, a college freshman, is completing his general education courses.

With success also comes acknowledgment and appreciation for the sacrifices Esperanza and Gabriel took to come to California. This recognition serves as key motivation for all of the Flores children as they work towards advancing their careers.

“Knowing what drove my parents to leave everything they knew behind to immigrate to the U.S. in order to foster a better living is what keeps me going every day,” Berenice said. “They left everything behind to come to a new country, not knowing about the food, language, and culture but knowing they would be able to live a better life than what they had.”

Although the family has spent more than 30 years living in California, their Oaxacan roots can be seen in the colorful tunics worn by the females of the family — known as “huipils” — to the Oaxacan-style mole sauce and cheese that accompanies most meals.

“Even though we are U.S. citizens, I think it’s still important to bring a piece of Oaxaca in our house,” Esperanza said. “That way, my kids can hopefully continue cooking the same recipes and holding the same traditions when they are older.”

The first time I traveled to Nuevo with my girlfriend Jennifer to visit her family, I immediately saw how different it was from the massive Los Angeles area I was used to. Cows and horses casually walked alongside cars, miles of empty land occupied most of the town, and there was only one place to buy groceries in town at a small Liquor store. Although I’ve never visited Oaxaca, I like to imagine that parts of the state

share similar characteristics to my girlfriend’s hometown.

To members of the Flores family, maintaining the culture brought over from Oaxaca is a source of pride that reminds them of where they came from. They plan trips to go back to visit family at least once a year, sometimes several times so that Esperanza and Gabriel can care for

To members of the Flores family, maintaining the culture brought over from Oaxaca is a source of pride that reminds them of where they came from. They plan trips to go back to visit family at least once a year, sometimes several times so that Esperanza and Gabriel can care for

their parents.

“I am proud of my Oaxacan roots and to know that traditions my parents and grandparents grew up with are still alive today,” Berenice said. “My family and cultural history is something I hold very close to my heart and I know I will keep traditions and stories alive to share with my children someday.”

Although I have never visited Oaxaca, I get a sense of the rich culture every time I spend a weekend with the family. It also gives me a chance to appreciate the difference of their culture compared to my family’s culture. The Flores’ house can easily reach 50 or 60 people at family parties, whereas, at my house, we rarely have more than 10.

To Eduardo, there are a number of qualities that make Oaxacans special.

“From my observations, Oaxacans enjoy celebrating festivities large or small, they love listening to live music and dancing and they appreciate being in the company of others,” he said.

Professor Flores-Marcial believes that’s only some of the ways Oaxacans connect to the motherland.

“There are strong ties to the communities we come from and many of these Oaxacan communities have organizations here in the U.S. that further build community, empower younger generations, and allow older generations to teach languages, culture, and history to the youth,” Flores-Marcial said.

As the Flores family takes further steps toward success, it’s clear that Oaxaca will always have a special place in their hearts.

“I am so proud of my children and what they have accomplished since they started college,” Esperanza said. “To me, seeing them succeed makes me realize that my husband and I have succeeded as well.”

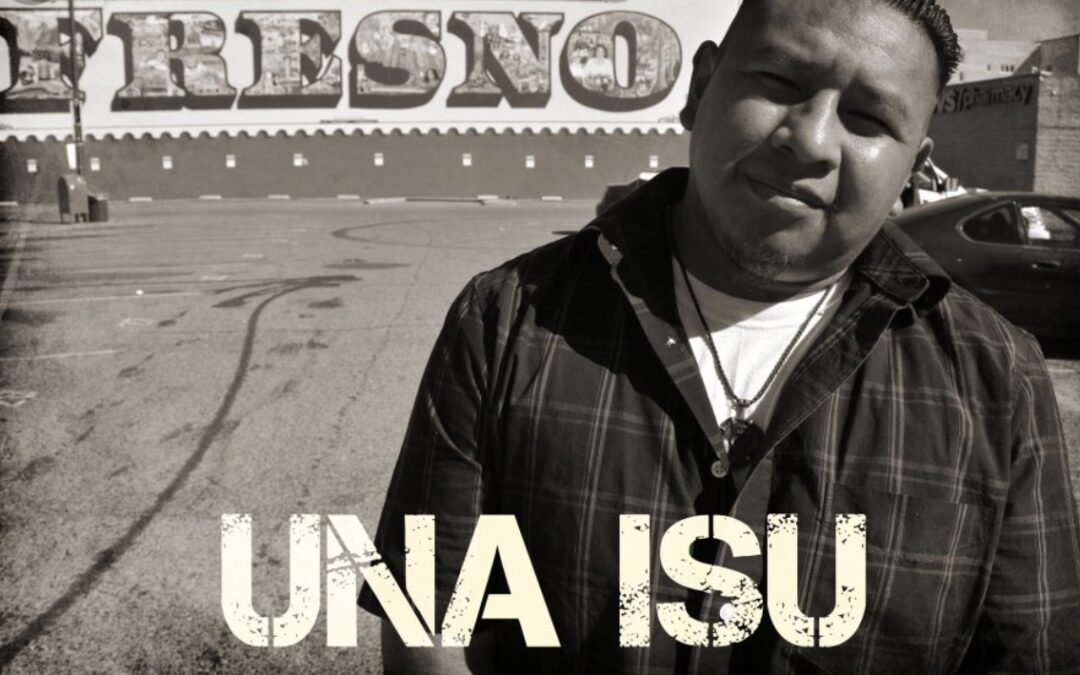

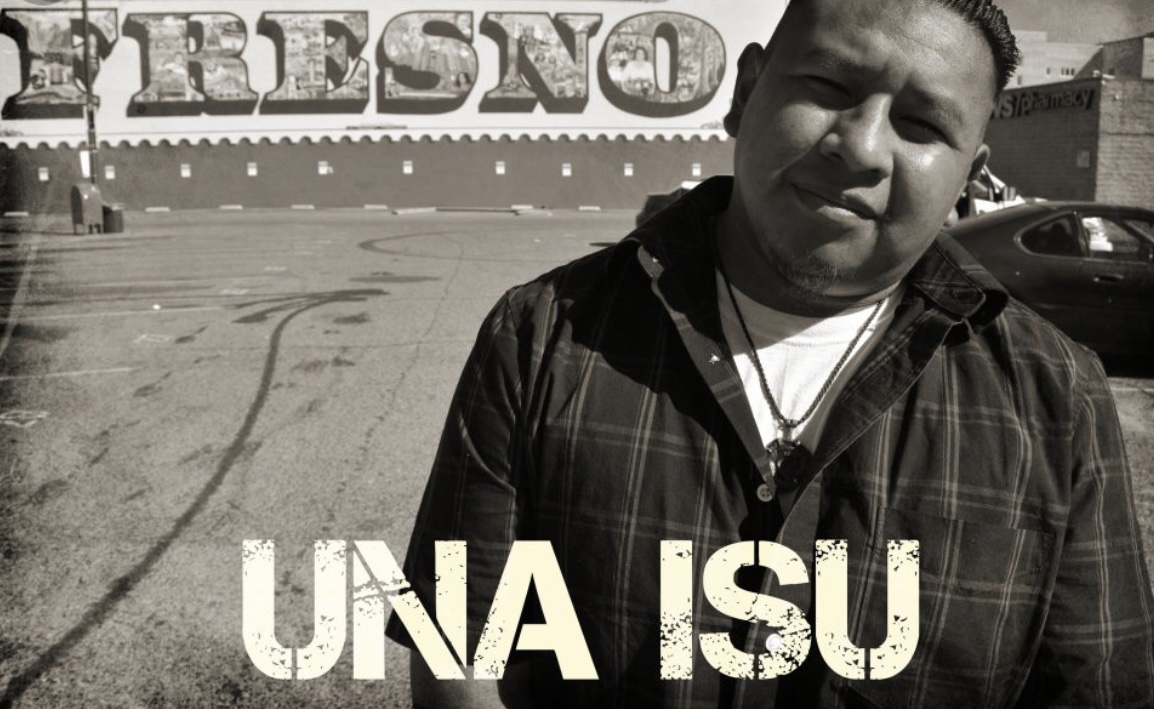

Una Isu es su propio equipo. Gracias a Internet ha podido promover su música usando SoundCloud, YouTube, Facebook e Instagram para promoverse. Él trabaja independientemente y no tiene contratos con ninguna compañía de música.

Una Isu es su propio equipo. Gracias a Internet ha podido promover su música usando SoundCloud, YouTube, Facebook e Instagram para promoverse. Él trabaja independientemente y no tiene contratos con ninguna compañía de música. Para Una Isu, es muy importante rapear en mixteco porque quizás jóvenes que lo escuchen a él van a ser motivados para también practicar sus lenguas.

Para Una Isu, es muy importante rapear en mixteco porque quizás jóvenes que lo escuchen a él van a ser motivados para también practicar sus lenguas.

Hablar de Federico Jiménez es hablar de uno los impulsores, defensores y promotores de las culturas indígenas mexicanas más importantes de México y Estados Unidos.

Hablar de Federico Jiménez es hablar de uno los impulsores, defensores y promotores de las culturas indígenas mexicanas más importantes de México y Estados Unidos. Ante las continuas amenazas contra su vida, los padres de Federico lo enviaron a Oaxaca con más equipaje que un cartón donde acomodaron la poca ropa que tenía. ¨Mi padre consiguió a través de un maestro que me aceptaran en una escuela que construyó el gobierno del Presidente Lázaro Cárdenas para los hijos de militares y los huérfanos. Todavía recuerdo que en medio de un abrazo que yo interpreté al principio como un acto de arrepentimiento por la dura disciplina a la que me sometió, me dijo: ¨No debes regresar.¨ Eso fue lo más doloroso para mí, recuerda con tristeza el ahora famoso diseñador.

Ante las continuas amenazas contra su vida, los padres de Federico lo enviaron a Oaxaca con más equipaje que un cartón donde acomodaron la poca ropa que tenía. ¨Mi padre consiguió a través de un maestro que me aceptaran en una escuela que construyó el gobierno del Presidente Lázaro Cárdenas para los hijos de militares y los huérfanos. Todavía recuerdo que en medio de un abrazo que yo interpreté al principio como un acto de arrepentimiento por la dura disciplina a la que me sometió, me dijo: ¨No debes regresar.¨ Eso fue lo más doloroso para mí, recuerda con tristeza el ahora famoso diseñador. En 1991, Federico hace historia en Estados Unidos al convertirse en el primer indígena mexicano elegido para formar parte de la Junta de Directores de los renombrados museos: South West Museum, Autry Museum of Western Heritage, (Ahora el National Center of the American West) y del Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos, Nuevo México.

En 1991, Federico hace historia en Estados Unidos al convertirse en el primer indígena mexicano elegido para formar parte de la Junta de Directores de los renombrados museos: South West Museum, Autry Museum of Western Heritage, (Ahora el National Center of the American West) y del Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos, Nuevo México.

Las primeras palabras de Martínez fueron en zapoteco. Aprendió zapoteco de su familia cuando era un niño.

Las primeras palabras de Martínez fueron en zapoteco. Aprendió zapoteco de su familia cuando era un niño.

Esto dificulta más no sólo navegar la sociedad norteamericana, sino también crea un gran reto tanto para estas personas como para las instituciones que proveen servicio público en entenderse. Por ejemplo, en el servicio de salud y en el sistema legal, entre otros, muchas veces la comunicación ha sido un gran reto. Uno de los retos principales para aquellas instituciones que proveen servicio al público es desconocer que en México se habla varias lenguas originarias, alrededor de 68 familia de lenguas. Esto ha sido el caso de las lenguas zapotecas, por ejemplo, en varios casos me han contactado desde hospitales, prisiones y cortes de migración para ser interprete de personas de habla zapoteca que requieren un traductor. Sin embargo, cuando les pregunto, al personal de las instituciones que necesitan comunicarse con sus clientes, de la variante del zapoteco que habla la persona que necesitar un intérprete, siempre las desconocen. Esto es el resultado de la falta de entender que el “zapoteco” no es una lengua en sí, sino una familia de lenguas zapotecas. Esta familia de lenguas lo hablan casi medio millón de personas en el estado de Oaxaca, además de los que lo hablan en la república mexicana, como en la Unión Americana. Este grupo de lenguas que le han llamado zapoteco, derivado de la palabra tzapotecatl en náhuatl y castellanizado por consiguiente es necesario que las deferentes instituciones que proveen servicios sociales y de intérpretes entiendan lo que llamamos la lengua zapoteca no es una lengua en sí. Entonces pensemos que el zapoteco es como la lengua romance. En otras palabras, no decimos que hablamos la lengua romance, sino que decimos que hablamos el español, portugués, francés, etc.

Esto dificulta más no sólo navegar la sociedad norteamericana, sino también crea un gran reto tanto para estas personas como para las instituciones que proveen servicio público en entenderse. Por ejemplo, en el servicio de salud y en el sistema legal, entre otros, muchas veces la comunicación ha sido un gran reto. Uno de los retos principales para aquellas instituciones que proveen servicio al público es desconocer que en México se habla varias lenguas originarias, alrededor de 68 familia de lenguas. Esto ha sido el caso de las lenguas zapotecas, por ejemplo, en varios casos me han contactado desde hospitales, prisiones y cortes de migración para ser interprete de personas de habla zapoteca que requieren un traductor. Sin embargo, cuando les pregunto, al personal de las instituciones que necesitan comunicarse con sus clientes, de la variante del zapoteco que habla la persona que necesitar un intérprete, siempre las desconocen. Esto es el resultado de la falta de entender que el “zapoteco” no es una lengua en sí, sino una familia de lenguas zapotecas. Esta familia de lenguas lo hablan casi medio millón de personas en el estado de Oaxaca, además de los que lo hablan en la república mexicana, como en la Unión Americana. Este grupo de lenguas que le han llamado zapoteco, derivado de la palabra tzapotecatl en náhuatl y castellanizado por consiguiente es necesario que las deferentes instituciones que proveen servicios sociales y de intérpretes entiendan lo que llamamos la lengua zapoteca no es una lengua en sí. Entonces pensemos que el zapoteco es como la lengua romance. En otras palabras, no decimos que hablamos la lengua romance, sino que decimos que hablamos el español, portugués, francés, etc.